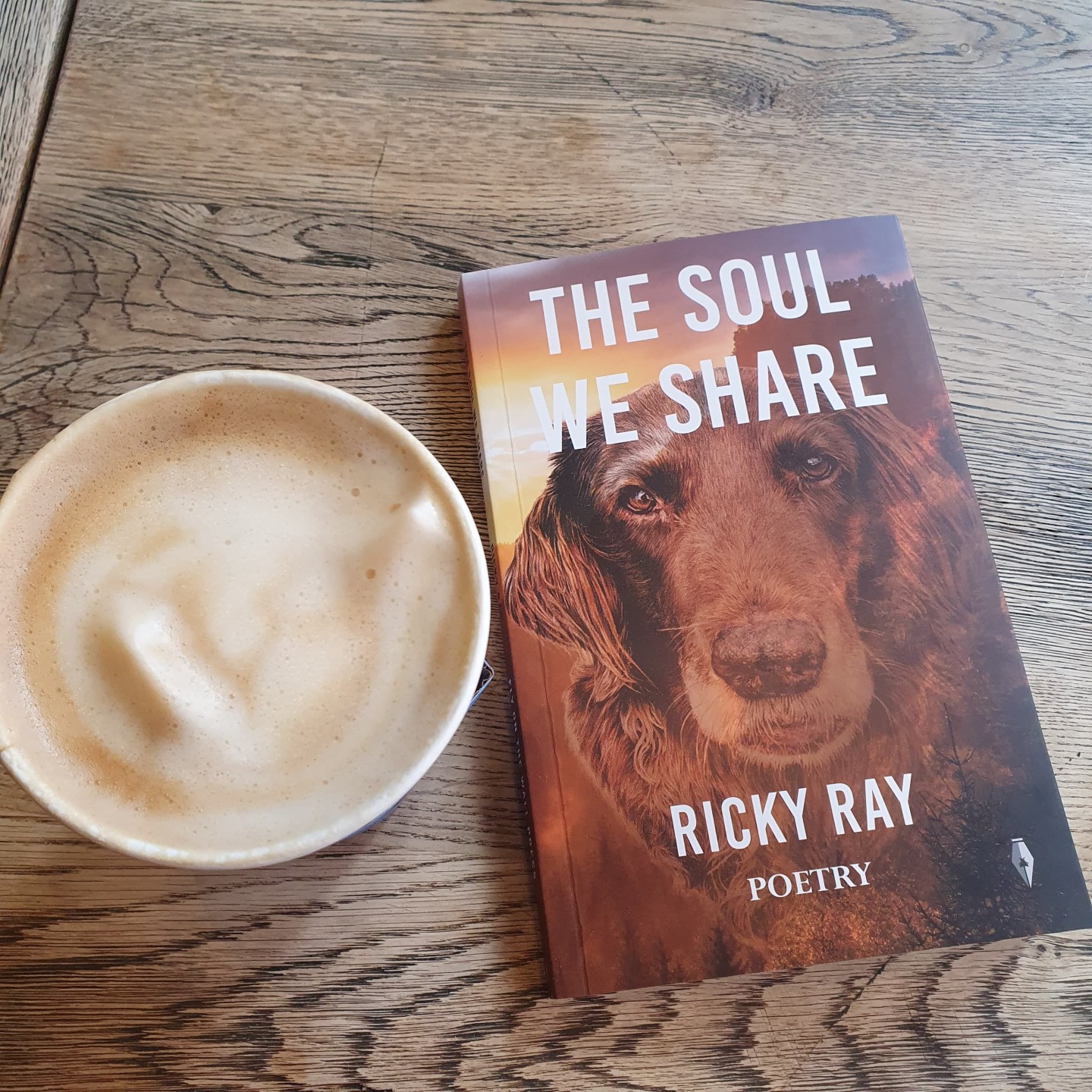

Interview with Ricky Ray

I read books like it was a form of breathing.

Your collection is sectioned like a journey through song, could you tell me a little bit about your thought process behind this unique structure?

“Hi! Thanks for engaging with the book and asking nuanced questions. I’ll tell you a little story.

I think a book has multiple kinds of poems. Word poems, page after page. Feeling poems, which run through multiple pieces like a recurring heartbeat, or a shared soul, or the energy one body passes to another—a sense of something happening in the way the poems relate and interact: where they came from, how they sing, both individually and communally, how their voices form resonances that string the book together, and dissonances that strum the tension of those strings across the pages. Then there’s the poetry of design, in the cover—which is the first poem a reader encounters—and in the font choices, the layout, the way the front matter greets a reader and the way the back matter wishes the reader farewell.

Another kind of poem in the book is the table of contents, or the line-by-line congregation of titles. One of my mentors taught that the table of contents can read like a poem, and is ripe for intentional refinement. I’d go a step further and say the contents page is always a poem, fully fledged, open to as much careful crafting as any of the verses, or open to letting the book’s arrangement create the contents poem on its own. Or a little of both. I like that any of the titles can be an invitation towards a different starting point. I love that a book of poetry never has to be read front to back. It can be, is made to be, but there’s always the option to choose your own adventure, and the contents poem offers the many paths one might take.

Yet another poem in the book, akin to the feeling of soul that runs through the poems, is the book’s structure, which participates in the structure of existence itself, nature herself. Poetry, to me, is the way nature moves. Atomically, celestially, relationally, intimately. Moves with exquisite creativity and glorious patterns. When we look at the etymology of the word poetry, it roughly means to make, to create. Mother Earth is a maker, a poet, a poet of geophysical movements, a poet of species. Grandmother Universe is a poet, a poet of planets and stars, solar systems and galaxes, mysteries and infinities, all-pervasive. Their collaborative poetry literally shapes our lives, literally is the process of life itself, a process we’re fortunate enough to be part of, living poetry, and given the chance to contribute the artistry of our own lives and lines to their Earthly and Universal verses.

I’m telling you this because I think poetry is the music of movement. And I think symphonies are one version of humanity’s musical talents approaching a natural limit. A gesture of deeply devotional design made in honor of the patterns that allow us to sing. To hear. To feel. My beloved dog Addie taught me how to feel these poems, then to write them down.

So when I asked the soul that Addie and I and Mother Earth share what kind of structure the book might take, the answer came slowly, over years. I love symphonies, especially Mahler, and especially Mahler’s 7th. It’s a bit chaotic, rather intense, but full of so much feeling, it floors me every time. I wanted to honor that love for him and his work, and Earth and her works, and the poems Addie and I lived into being, so I sought to intuit a structure that aligns with all these interwoven rhythms.

To give the reader a sense of what we’re talking about, the book’s structure looks like this:

- Title Page

- Dedication Page

- Prelude

- Movement I

- Movement II

- Interlude

- Movement III

- Movement IV

- Movement V

- Coda

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

At first, I realized that the main parts of the book were not just sections, but movements, ways of being and living, with unique energies that build in progression. And I’ve always been fond of books of poetry that seem to have little preludes at the start, little orienting compasses—murmurs, intimations, a glimpse of the architecture about to be revealed. Poem 0.5, prepping us for poem 1. “The What of Us” felt like that prelude, its rhetoric setting the philosophical and emotional tones, the sections offering brief glimpses into the various kinds of weather in the book’s world, a world full of the selves we contain and the selves we belong to, my organism trying to turn feeling into song at the crossroads of that inner and outer selving.

The interlude came to me late, after the book was struggling for years and I couldn’t quite figure out what was missing. It’s essentially a small lyric essay. After 20 years as a poet, I began to write non-fiction, a cross between science, spirituality, memoir and eco-mysticism, something I call spiritual storytelling, another kind of poetry, a poetry of belonging, reminding us of the selves we belong to beyond our person, and the responsibility to extend our radius of care to the places we call home.

Movement III is a long, serial poem, kind of a counterpoint to the Interlude, which I now realize I might have titled Interlude II, but then the book wouldn’t have five movements, like Mahler’s 7th, so I think my original instinct was right. I rarely write poems of such length, and this was the only poem I wrote in a year, a poem that showed up and asked to be written all of a sudden on a single afternoon. I love those sudden thunderstorms of poetry, human consciousness buzzing like a beehive and barely able to keep up, and it’s probably a crucial ingredient of their magic that the storms so seldom occur.

To bring the composition to a close, like preludes, I love codas, the satisfying little extras that sometimes happen when the soul wants more. The encore. The last hug from a friend who’s moving away. The last, long look at a land one leaves, lingering until it almost hurts, but hurts in a good way, knowing you won’t return, but knowing the land will be alive in you wherever you go. The last days with a dying beloved, like Addie.

Addie, my soul dog and co-author, fought and bested brain cancer for over two years before she died. She had more living and loving to do. More to teach me about life. So she said fuck cancer and kept going. And when she lost some ability or other to cancer, she focused on the ones she still had. Then, about four months before the book was finished, she almost died. She had developed three more types of cancer. She had a 3+ hour seizure. But still, she wasn’t ready to go. She wanted to live to some limit only she kept in sight. And I was grateful. She astounded the doctors and gave us four more months to live in the love of goodbye. It was sweet. It was heartbreaking. It was so intimately poignant, every day, her body slowly failing and her spirit letting us do for her what she couldn’t do for herself. These months were the book’s real coda.

The coda in the pages, “The Last Walk,” was, for me, a spiritual necessity. It’s what I needed in order to cope at the moment of her death. It came to me—one of those rare storms—probably two years before she died. The only poem that has made me cry over and over again. I read it to her, in the minutes before her heart stopped, and I felt her magnificent spirit in every word”.

Do you have any first memories of poetry, or an indication of what brought you to exploring this form of writing?

“Memory is mostly shadow and mystery for me. I have aphantasia, the inability to visualize, which occurs along a spectrum, and I’m closer to the end of the spectrum where I can feel things but not see them. Dimly at best. I don’t mind, I kind of like dwelling in and as mystery, but it means little is available for in-depth recall. Nevertheless, feeling for what I can make out of the faded snapshots of life, I suppose the seeds of poetry began to take root in a few different ways. I grew up poor, like hungry poor, like years with no electricity poor, like running a hose from a neighbor’s faucet so we could take a bath poor. But I was rich in my relationship with my childhood dog, Rascal, and rich in books from the library, and rich in music, my Walkman tuned into the streams of music flying through the air. I read books like it was a form of breathing. I listened to music nearly everywhere I went. I sat with Rascal in the yard and felt us deeply immersed in the movements of the grass, the weather, the heat, our love, the day. Rhythms and deeply felt relationships were how he, my dad and I got by.

But I wasn’t ready to be a poet. I loved reading but didn’t care for English at school. I loved math and thought I’d be a mathematician. The transition happened in my late teens: through the genius of mid-‘90s hip-hop lyrics, through Rilke’s stormy soul, through failed love notes I wrote to girls, through poetry saving my neck. I’d walk around the library and pluck books randomly from shelves. At some point, that shelf included poetry. And I was reading poetry often when I went to college, heartbroken after a breakup, losing interest in engineering, in life. I began to dabble in drugs, and one night, I mixed the wrong ones and accidentally overdosed. Luckily, my body didn’t quit. Luckily, kind souls found me and ferreted me to the hospital. And when I woke up, poetry was there, offering me a lifeline, a way to heal and a way to care, a way to develop a more attentive and a more deeply felt relationship with the world, and that was exactly the medicine I needed. Poetry saved my life, so I vowed to give my life to the art in return, in the hopes that my art might one day do for others what the works of my predecessors did for me. And 25 years later, I’m still trying to keep that vow”.

In your poem ‘How to Go On’ you talk of nature’s power to heal. Do you find poetry has a healing nature too?

“I’d like to unpack the phrasing here. There seems to be an implication that sitting in a field, conversing with blades of grass, asking them to teach me how to overcome one of the moments of defeat that threatens to do me in—blows they take and rebound from on the regular—is invoking nature’s power to heal. I think that’s true—I agree.

But I worry that there’s an implication beneath this one, an implication that says were I doing the same on the floor of an apartment, I wouldn’t be invoking nature’s power. (I would.) An implication that nature is the green thing at the edge of our manufactured things. Perhaps that’s not implied, but I want to be clear, for this point is vitally important.

To me, nature is the way things are, the all-pervasive Earthly and Universal movement, and all things are natural, from quarks to buildings, from peat to plastic, and this sense that humankind can somehow excise itself from nature, and act upon nature as an external force, is the very delusionary thinking that lands us in the mess of destabilizing ecological processes because we blinded ourselves to ourselves to our roles within those processes from conception to grave. We’re not special. We’re not other. We’re one in a long line of species participating in Earth’s process of life. 99% of species are extinct, but gave rise to us and all the ones we know and love. We and our companion species will give rise to countless others. Our successor species are taking shape in us now. We might be disruptive, might be addicted to a very limited sense of what and how we are, but we’re still natural, still nature, still the Earth herself, still making mistakes and self-correcting and unfurling the billions-year-old story of life, a few pages of which our species is lucky enough to grace for a while.

Apologies for the eco-sermon! But I wanted to lay the groundwork for saying that I believe the power to heal, in any capacity, in any phenomena, is nature’s power. As for poetry’s power to heal—indeed: it saved me. In my wife’s culture, people quote poetry to one another across the dinner table. In some countries, poetry can fill stadiums. One of the earliest poems I shared on the internet triggered an email: a woman asked if she could read the poem at her mother’s funeral, with thousands in attendance, said it was what she had been struggling to voice but couldn’t. I don’t remember the poem but I remember the feeling of being able to offer her the words, the medicine she needed and the medicine she wanted to offer the grieving, and that memory has often been one of the very few things that kept me going.

Broadening the perspective, I believe species are Mother Earth’s poetry, a kind of poetry she conjured out of chemistry and physics, and that one of art’s greatest powers, whether in our hands or hers—one of its reasons for manifesting—is its medicinal nature: a reminder of the infinite relationships flowing through and forming us all the time, and an invitation to re-root ourselves in the creativity that made us, that makes us—the creativity that’s always near to hand, inviting us to take part”.

Poems in this collection such as ‘Ache, Solo #21’ showcase what a beautiful relationship you share with Addie. Did you always know you were going to write a collection celebrating her companionship?

“I didn’t. Addie and I were living it—she was teaching me how to live poetry—and I was writing those poems down, but the realization was slow coming. Even when I shaped the book at first, which had many Addie poems, my mentor Craig Morgan Teicher had to point out that she was the heart of the book, that the poems about her offered a unique side of me, and that the collection was naturally inclined to center around her. Craig is great at subtle insights, gentle nudges that lead to substantial transformations. It’s odd, to need it pointed out. But sometimes you’re so immersed in what’s happening it’s hard to see it.

Addie and I lived so closely together—every moment, every breath—we eventually began to move like a single spirit spread across two bodies. I could read the rhythms and desires in her breath like a living book. She could read my body language and habits like the hours of the day. Life wasn’t something we did individually. My number one priority was to be with her, to do whatever I could not to separate the pack. We were almost never apart, from morning to midnight, for 10 years, and I spent the last 5 years of her life sleeping in a makeshift bed next to her on the floor.

And Addie was spending that time not just enjoying our deep and loyal companionship, but teaching me how to live, how to deal with my own failing body, as hers was failing her, and how to focus on the life available to us, any instant of which is filled with wonder, interest and relationships waiting to happen. She taught me to live in attentive relationship with every field, every pee-spot, every morsel, every body of water, every spark of sensation that alights in the soul. And she taught me that soul isn’t merely some energetic trace within, it’s an animacy that we both possess and inhabit, something we actively shape in our living and being, something we share and belong to, as much as something we have and behold. To share a soul, and to live in honor of that shared reciprocity, to feel ourselves kin with every phenomenon and creature, responsible to the Earth and as the Earth—that was one of Addie’s many lifelong teachings.

Those teachings took place over the course of a decade, a decade in which this book was taking shape, so of course it is Addie’s book as much as it is mine. She was there when it began, is a shared presence in every line, and she lived until shortly after the last edits were made and the book was sent off to print. I’m heartbroken. Learning to live life in conversation with her spirit but not her body is a sobering, deeply quieting, difficult experience, but I’m so glad she gave us the moments that made the book possible, a book through which my love for her gets to continue to grow”.

Do you read poetry yourself, and if so is there a particular poem that sparks inspiration for you?

“That’s a chilling question, the idea that someone could write poetry but not read it. I suppose it happens. At least in the sense that some people write or compose poems and don’t read or listen to poems composed by other humans. I’d argue that they still experience poetry in song (and in their bones), but let me not stray too far afield.

Yes, being a human poet means, I think, two essential things: imbibing poetry and participating in its creation. I want to move away from the language of reading and writing, because those are only two, limited ways of partaking. Lots of poetry exists on recordings. Or is memorized in people’s hearts and heads. Or happens quite unexpectedly in the course of a conversation. To hear the poetry all around and within us, I think that’s one of the gifts of becoming a poet. And for those who cannot read, and for those who cannot write, I’m glad poetry is still accessible in many, many forms.

As for a poem that sparks inspiration, well, I could go on for days. I should, at some point, probably put together a commonplace book, a personal anthology for sharing. Czeslaw Milosz’ did in the anthology A Book of Luminous things, a book I first read 25 years ago, a book which remains one of the most inspirational collections I’ve ever encountered”.

As for me, let me offer a little journey, and since I’ve already spoken at length, I’ll let the poems sing for themselves:

Lisel Mueller – “Monet Refuses the Operation”

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/52577/monet-refuses-the-operation-56d231289e6db

Richard Hugo – “Glen Uig”

https://poets.org/poem/glen-uig

Brigit Pegeen Kelly – “Dead Doe”

https://kenyonreview.org/kr-online-issue/in-memoriam-3/selections/brigit-pegeen-kelly/

Ross Gay – “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude”

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/58762/catalog-of-unabashed-gratitude

Mary Oliver – “Gravel”

Some poets find the idea of sharing themselves on the page incredibly vulnerable. Do you ever write poetry which you intend to never share? And if you do write for an audience, do you ever find catharsis in sharing your work?

“To the first question, no. I’m always open to sharing, and I believe vulnerability is a fundamental aspect of the way I practice the art. That’s not to say it’s the right mode of practice for others. Just how it happens for me. And I never undertook writing poetry for my own sake. I started by writing love notes to girls. Those notes were failures. As were most of the poems I’ve written. But when I became serious about the art, after it rescued me and I devoted my life to it, I wrote in the hopes of making the medicine someone might need. I write to be of service, and I love that orientation, but it’s only one of the many good and right orientations available. As for catharsis, it’s not something I ever have in mind, but it certainly happens, and I suppose it’s one of the benefits the medicine offers—to poet and imbiber alike”.

Do you have any advice for poets hoping to form a collection of work, who are unsure where to begin?

“The mantra I was lucky enough to formulate early on, and which has been the foundation of my engagement with the craft, is to “read widely across times and cultures, and deeply within areas of interest.” You don’t have to take workshops, get degrees. There’s an industry built around it, and it’s a good path if it works for you, but it’s completely unnecessary if it doesn’t. That said, if you want to be a poet and publish collections, take the responsibility seriously. If you can read, read every era, every culture, every kind of poetry you can get your hands on. The teachings, the possibilities, the soul of poetry circulating throughout the vastness of our species is in the books (and in the woods) even more than it’s in the classroom. And the more exposure you have to different kinds of poetry, the more you can understand poetry itself—the more you can see where it’s been and where it might ask you to go. (You don’t have to buy the books, btw. Use the libraries. Sit in bookstores. Use Libgen or Soulseek. And if you need help, feel free to ask me how.)

The second half of the path is simply “to write.” And I mean write your ass off. Write and write and write until the poetry becomes not merely something you do with words, but a way of perceiving and engaging with the world. Write until poetry takes up residence in your blood and feels like it’s always been there, even if we spend much of our lives unaware. But I would caution against feeling beholden to writing or to a specific pattern of practice. You don’t have to write every day. You can, and that might work for you. But you can think about poems for weeks or months, and write only when the thinking cannot help but spill over into words. You can not write at all. You can compose poems in your head and memorize them and create an oral art. An oral body of work you perform whenever the occasion feels right.

I think my best advice would be to try to listen to the poetry in the world, to live in the poetry of feelings for a while, and then, to work on putting those feelings into words. This is what I learned from Addie, and my poetry grew under her guidance more than I can say.

And when you’ve got enough poems to work on a collection, think about all the kinds of poems a book contains, the kinds I talked about in my first answer. Most of all, think about how the poems relate to one another as beings with their own tendencies and characters. Try imagining what the poems would think of one another, and if they lived in a village, which poem would live next to which, and how they would go about their lives. Then imagine what arrangement would convey the soul of that village, even after the villagers are long gone”.

Lastly, if a reader could take away one thing from the collection ‘The Soul We Share,’ what would you hope it would be?

“That, as Addie taught me, as Mother Earth has taught me, we share a soul. That we are a majestic nexus of selves. That each of us is simultaneously a quark, atom, cell, organelle, organ and organism; a person, family, community, species, life itself, Mother Earth herself, and Grandmother Universe, from big bang to the end of times, across many galactic incarnations. And most importantly: that in this shared soul, we are endlessly responsible, responsible to every layer of the selves we contain and the selves we belong to—responsible to those selves, as those selves, every bit as much as we’re responsible to these fleshly pots of human. It’s an almost overwhelming responsibility, but it’s also the gift of care”.

You can order a copy of, The Soul We Share from Fly on The Wall Press.

https://www.flyonthewallpress.co.uk/product-page/the-soul-we-share-by-ricky-ray