The atomic history of Kiritimati - the tiny island where humanity realised its most lethal potential

Originally published on The Conversation

By Dr Becky Alexis-Martin, Lecturer in Political and Cultural Geographies at Manchester Metropolitan University

Ron Watson was just 17 when he experienced his first nuclear weapon blast. A British soldier from Cambridgeshire, he had completed his training in the summer of 1957 before departing on that fated tour with the Army Royal Engineers on Boxing Day.

After the excitement of leaving on a specially chartered train, “all thousand of us”, and then sailing across the oceans, he was wholly unprepared for what awaited him in the tropics.

The now 79-year-old told me, over a cup of tea in my office, that the first thing to strike him was an unbelievably bright light. “I had my back to the explosion,” he continued. “My eyes closed with my hands covering them. I clearly saw the bones in my hand, just like you see them if you look at the results of an X-ray.”

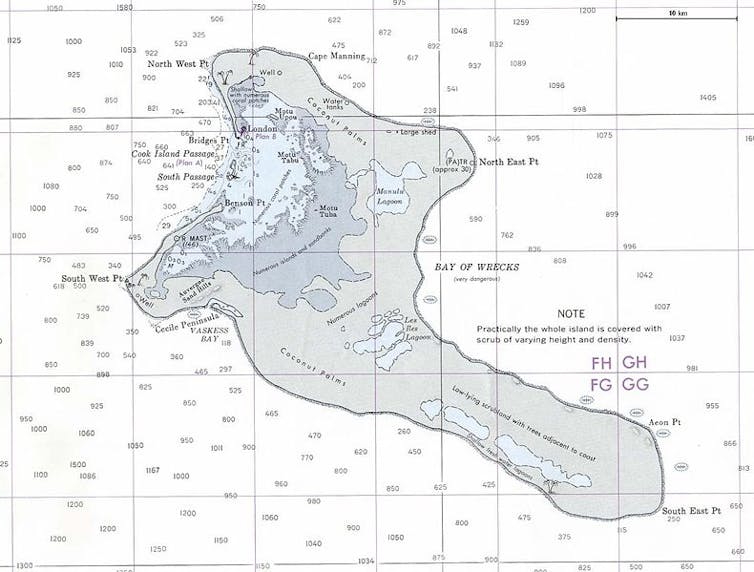

This was April 28 1958, and he had witnessed the British army’s Operation Grapple Y H-bomb test. He had been posted to Kiritimati (Ki-ris-i-mas or Christmas) Island, one of 33 low-lying islands that constitute the nation state of Kiribati in the Pacific. It’s a stunning coral atoll with crystal-clear waters, blue skies – and a shocking legacy of British military occupation.

Kiritimati was deemed a “pristine” place by the military when it was used for nuclear weapon tests during the Cold War. While South Pacific islands like Kiritimati were often described as uninhabitable wilderness by the military officers who chose them, this was often far from the truth. Local people were forced from their homes, at best; or were left in place potentially to be exposed to ionising radiation, at worst.

Between May 1957 and September 1958, the British government tested nine thermonuclear weapons on Kiritimati for Operation Grapple. Then, in 1962, the UK cooperated with the US on Operation Dominic, undertaking a further 31 detonations on Kiritimati.

About 20,000 British servicemen, 524 New Zealand soldiers and 300 Fijian soldiers were deployed to “Christmas Island” from 1956 to 1962. These men were unwittingly placed in harsh conditions with limited resources, while undertaking the work that would cement Britain’s place in history as a thermonuclear power.

The long-term impact on their lives and families largely has been ignored. So has that on local people who lived, and still live, across the islands of the Pacific Proving Grounds (the name given by the US government to sites of nuclear testing), where humanity realised its most lethal potential, and whose tiny homeland is once again placed in peril by foreign powers – this time by climate change.

For the last few years, I have been researching the intertwined lives of both British nuclear test veterans and Kiritimati communities, as they continue to try to make sense of their experiences. These are their stories.

Atomic atolls

Teeua Tetua was just three when she was blindfolded with a rough cloth by her mother. They then braced themselves for the Grapple Y explosion. She was very young, but still recalls being frightened in her mother’s arms during the deafening blast.

Last year, Teeua – now 64 and the chairwoman of the Association of Nuclear Victims in Kiritimati – welcomed me into her home, which is strung with cowrie shells collected from the beach, and also serves as a local children’s nursery. Her friends and I rested on our stomachs on woven palm mats on her veranda and chatted about their experiences.

Teeua told me that she worries about the long-term health effects faced by the islanders following the nuclear weapon tests. “There has been no compensation,” she said. “I worry about cancer and other effects to health – this is why I campaign.”

Philomena Lawrence, another islander from Kiritimati who now lives in the UK, told a similar story. She is too young to remember the nuclear weapon tests, but recalls the impact of British military occupation. Kiritmati was still a British colony at this time, and this presence had a particularly profound effect on her life as she met her British husband, a development officer for the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, on the island in 1970. They lived together on the island for 15 years, before moving to the UK.

I met her at her home in Kent before travelling to Kiritimati. She talked to me about island life, put me in contact with some of her friends, and gave me packages of books to take to the island’s children.

“There was little understanding of harmful effects,” she said. She recalled how islanders were taken to a boat to watch a Disney film to distract them during one test and how they were also told to gather on a tennis court covered by a tarpaulin for another. “The locals were terrified,” she added.

She described how she knew of two women who were born with birth defects after the tests, and how their father, Tonga Fou, who died in 2009, had worked with the British as an unrecognised nuclear test veteran. Tonga Fou had recorded data from the tests in red notebooks. “He shared the notebooks with his grandchildren like a bedtime story,” she said.

Island life disrupted

I went on to speak to a further 14 Kiritimati islanders to learn about their lives and experiences of nuclear weapon testing. All of the islanders that I spoke to who recalled the tests also remember being frightened and uncomfortable. They described the tests in terms of confusing events, crowds, megaphone countdowns and deafening noises.

Taabui Teatata was 11 at the time of the first test. She described to me how her community was unexpectedly moved at midnight by a military commander beforehand. She was frightened, but remembers the army commander who moved her and her family telling her: “Don’t worry, you’re safe – this is the British military.”

She described being loaded onto a ship and taken offshore before the tests, and being too frightened to talk. She said: “It was very crowded, it was meant for cargo and there was no room for children like me to play. There was no space, we were treated like animals.”

Kimaere Kiiba, 73, was also 11 when the first Grapple H-bomb was detonated. As we sat on the raised wooden platform of his corrugated iron home on Kiritimati, discussing the nuclear tests, he told me:

I was surprised to see what was happening, because we had never experienced it before … When we heard that the British were coming to Christmas Island, when the ship anchored, we all went to the beach to watch and wonder what would happen.

He did not understand what was happening, and over the years has questioned whether or not the island elders truly grasped what the British were planning, prior to their arrival. He said: “Perhaps they understood, but they had no choice … We were afraid and very innocent. We didn’t understand how dangerous and bad for our environment the situation was.”

He also described the conditions that military servicemen lived in. “They had no kitchens, and ate out of cans,” he said. “The soldiers were nice to me, I gave them some fish. We were allowed to talk to them on the road, but forbidden to talk to them if we were at their camp.”

I also spoke to a 90-year-old woman called Buburenga Iotebwa. She was the oldest person I interviewed. She had migrated to Kiritimati with her husband from another island before the tests. She vividly recalled being corralled under a tarpaulin on a tennis court with many others during one early test. She developed sight and hearing impairments shortly afterwards.

She also described how local food was contaminated by the bombs: “You would get food poisoning, even drinking from fresh coconut. All fish except shark gave us cramps … We were given some medicine from the soldiers.”

While the islanders continued to eat and became unwell, the servicemen were ordered not to eat the local foods, because of these contamination concerns.

Military life

Many of the British servicemen who worked on the operation – and their families – were also left scarred for life, in some way, by their experience on the island. Men were traumatised by what they had seen, and by the culture of secrecy that surrounded their work. And after they returned home, they were damaged by the apathy that they received from the government.

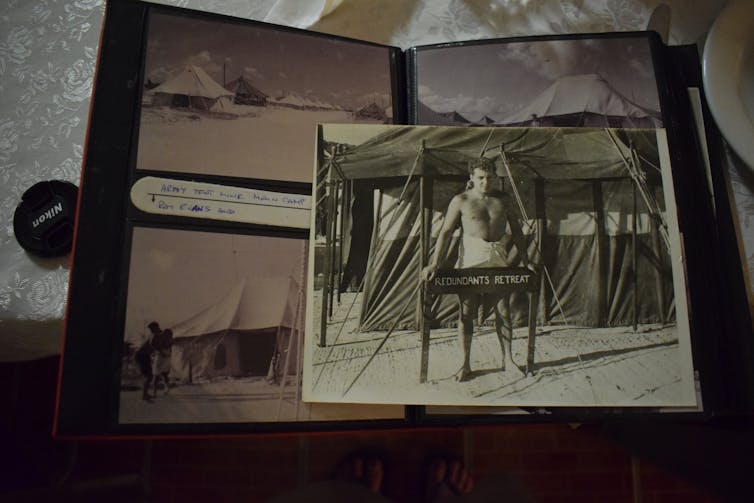

The experiences of the servicemen who were posted to Kiritimati were shaped by the conditions, risks and consequences of military life. Although they believe that it was the nuclear weapons that posed the greatest risk, their work presented many other hazards, including sunburn, sunstroke, accident, exposure to carcinogenic DDT, poor sanitation, dysentery and inadequate rations. Morale was low and several servicemen killed themselves.

Veteran descriptions of minimal protective clothing, line-up drills, and radiation sampling provide a vivid narrative of the realities of their work on Kiritimati.

Terry Quinlan, 79, who now lives in Kent, was 19 when he was deployed to Christmas Island for Operation Grapple. He told me how they lived in tents in intense heat and were “eaten alive by mosquitoes”. He continued: “People caught ringworm, some swelled up like balloons.”

His experiences of lax health and safety echo those of many nuclear test veterans interviewed during my research. He said that his section “witnessed five blasts, two A-bombs and three H-bombs on the beach in 1958”.

We had no protective clothing, I wasn’t even issued a pair of sunglasses. We were just told to assemble, sit down and to put our fists in our eyes. The officers were not with us, they had protective clothing and bunkers elsewhere. We were sworn to secrecy for life, and told that we must not discuss it with anyone. We received no medical examination when we left the island in 1962.

Terry went on to describe an injury that he received while witnessing a nuclear weapon test.

We were pushed along the beach by the blast and people’s backs were scorched. I was hit by something, I thought it was a bit of coral or something. Years later in hospital, I discovered that it was a foreign body. The doctors discovered a piece of shrapnel from the blast in my chest.

There was also limited interaction between servicemen and islanders. Robert McCann, 80, from Hampshire, talked to me about how the two communities were isolated, saying: “I never mixed with locals the first time I was there, I saw them, but only from a distance.”

This segregation meant that many of the young servicemen had no chance to get to know islanders, and this hid the impacts of the tests to local people from them. Many have since been dismayed to discover the consequences of their work.

The way that risks were managed has affected the veteran community’s understanding of their experiences. Despite assurances that the nuclear tests posed little risk of radiation exposure, they have had diverse repercussions. The true costs of the tests are only just beginning to emerge.

Understanding exposure

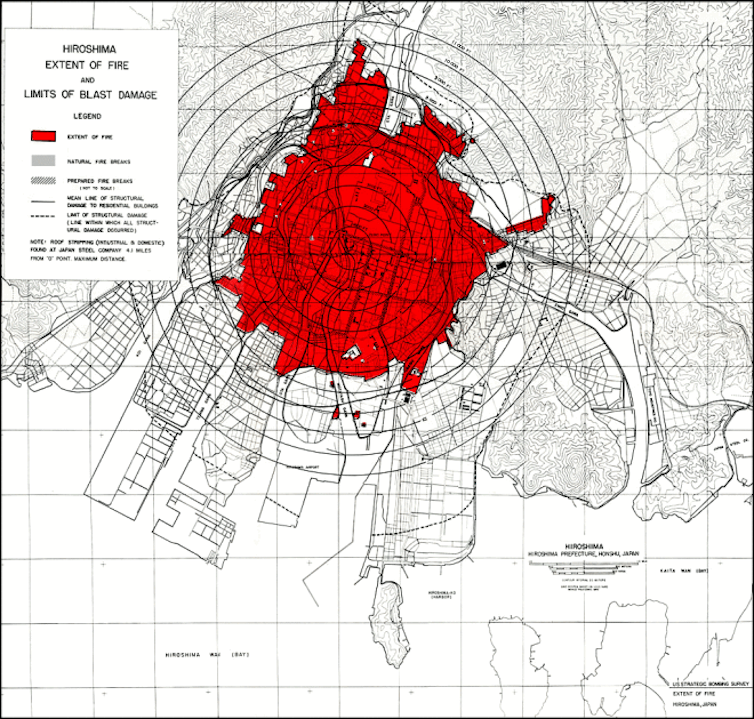

The general public first became aware of the health effects of ionising radiation after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, which killed 225,000 people. The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission was then established to undertake epidemiological and genetic studies of survivors. Approximately 200,000 people have been followed for 74 years, in the world’s longest public health study.

Military secrecy has meant that there was no equivalent long-term health study for nuclear test veterans. But in 1983, a study of 21,357 veterans was commissioned by the Ministry of Defence (MoD), conducted by the National Radiological Protection Board and Imperial Cancer Research Fund. This work discovered a slightly elevated risk of leukaemia and the presence of a “healthy soldier effect” – meaning that they were in some ways healthier than a control group.

But the results of state-commissioned studies are sometimes mistrusted. These studies also do not take into account the lived experiences and difficulties that are part of many nuclear test veterans’ lives. And to date, no long-term public health study has been undertaken for the people of Kiritimati.

Generations of harm

This is why I set out to explore their lives, and those of veterans’ families, exploring the lives of 67 nuclear test veterans, and 162 children and grandchildren. I discovered challenges of specialised aged veteran care, evidence of heightened perception of risk of radiation effects and impacts on well-being and mental health.

Concerns were raised by descendants about reproductive risks. Some daughters of nuclear test veterans had chosen not to have children due to their heritage. This attitude is usually only observed in families where there is a risk of severe hereditary health effects, such as cystic fibrosis.

Nuclear test veteran daughter, Susan Musselwhite, is one of many of the descendants I spoke to who attributes her health challenges to her father’s work on HMS Narvik, a control ship for Montebello Island and Grapple nuclear tests. He was a navy diver near Kiritimati at the time.

Susan, 39, from Devon, suffers from numerous conditions, including chronic migraine, thyroid issues, nerve damage, bowel and bladder issues and Grave’s disease and depression. She also had fertility and other women’s health issues from an early age. Over a cup of tea at her home, she told me: “I truly believe that I have these health issues because my father was at the nuclear weapon tests.”

Another interviewee, who wished to remain anonymous, described how she felt disconnected from her father’s experiences after his death at 41 from multiple organ failure. She said: “It feels difficult to know how describe my experiences … I’ve always been a daughter to the story about a nuclear test veteran. My dad.”

She told me how her early understanding was fused with grief and loss – and how as her understanding of the world grew, so did her understanding of the significance of working on the nuclear weapons programme.

I have recently watched footage of the Grapple tests in astonished horror. I cannot help but wonder: did he see this? Where was he? What did he see? What was it like? And what did he do aside from turning his back from the blast? Did this cause his death?

Coming together

These stories demonstrate the need for recognition and reparation for the injustices that the British state perpetuated against both veterans and Kiritimati communities during the Cold War. Both communities have sought such recognition – with limited success. Yet the voices of those affected are becoming louder.

The British Nuclear Test Veterans Association (BNTVA) is campaigning for medals for nuclear test veterans, to try to help them to gain state recognition. The scope of the BNTVA’s work has since expanded to include support for the people of Kiritimati who have been affected by the tests.

Meanwhile, the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty has outlawed all nuclear weapon testing since 1996. Kiritimati is also part of the South Pacific Nuclear-Free Zone. This means that nuclear warfare should never encroach on island life again. But the people of Kiritimati have not forgotten their experiences of nuclear imperialism and hope that the UN Nuclear Ban Treaty will be successful.

Healing can happen in quieter ways, too. In 2018, a group of five nuclear test veterans returned to Kiritimati to memorialise the 60th anniversary of Grapple Y. I documented this ceremony, which included a speech on pacifism from a local pastor and a talk by Teeua Tetua herself.

This was the first time that veteran and islander communities were able to connect, share their experiences, and look to the future.

While I was there, I discovered that in Kiribati, there is a tradition of collective responsibility. This is denoted by the phrase “bubuti”, which means a request from a friend that cannot be refused. This highlighted to me how much we can learn from these communities. The concept of bubuti deserves an international extension. Because globally, we must accept and respond to the long-term effects of nuclear weapons testing – and other impending threats, including climate change.

There is a long road ahead before parity, social and environmental justice are reached. We must provide adequate support, reparations and adaptations to both Kiritimati islander and nuclear test veteran communities, and provide them with the dignity and grace that they deserve.

This article is part of The Conversation’s Insights series.

The Conversation’s Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges. In generating these narratives, we hope to bring areas of interdisciplinary research to a wider audience.