Supporting people with learning disabilities

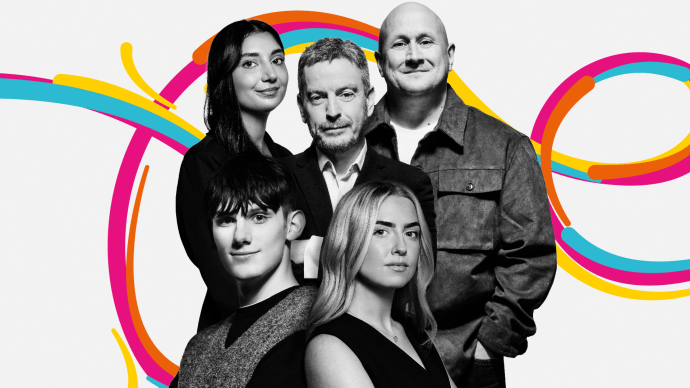

Chris and Sara image header

Standfirst

Professor Sara Ryan’s drive to support people with learning disabilities runs deep.

Her work helping people live full and meaningful lives was inspired by a heart-breaking experience with her son, Connor, who had autism and learning disabilities.

Main story

Lovingly nicknamed Laughing Boy, Connor Sparrowhawk’s death at an NHS unit aged 18 was entirely preventable, as judged by a court of law which found serious failings in his care.

Armed with that incontrovertible evidence and a justifiable sense of rage, Prof Ryan focuses her work on changing the way people with learning disabilities are treated.

“Connor went to that unit as a voluntary patient and died 107 days later because the staff let him bathe unsupervised, even though he had epilepsy,” she says. “It was devastating, but the way people supported us to get accountability was extraordinary.”

Prof Ryan’s campaign (#JusticeForLaughingBoy) and the groundswell of action from impassioned strangers focussed on positive change. Now, through Prof Ryan’s unshakable drive for action, Connor’s legacy lives on.

We need to involve people with learning disabilities, as well as the professionals who have the power to change things.

“I did quite a lot of soul searching,” she says. “I was already doing research in this area, but I realised we can’t just write an academic paper and assume the job’s done. We need to involve people with learning disabilities, as well as the professionals who have the power to change things.”

Case in point is Flourishing Lives, her project looking at how social care can better support people with learning disabilities to do the things they value – whether that’s feeling the wind on their face or listening to their favourite song.

Prof Ryan supported people with learning disabilities to present the project to decision makers including NHS England and the Care Quality Commission.

Our point was simple - the key to a good life is to have the opportunities to do the things you love.

“The challenge is finding out what those things are, however small, and ensuring they’re part of a support plan. One participant told us that ten minutes listening to Britney Spears can transform their day!”

Flourishing Lives strikes a note of optimism, but there’s still a way to go, as evidenced by related research.

Grown adults being left to watch TV all day, then put to bed at 5pm and denied a simple glass of water were just some of the shocking examples of poor practice witnessed by the researchers in a recent study.

Their assessment of home and day services for people with learning disabilities aged 40 plus found that few services adapted their approach for people as they aged.

“We knew things were bad,” says Prof Ryan, “but we didn’t anticipate the extent to which older people with learning disabilities are systematically denied the opportunity to age meaningfully.”

In moves to improve life for the approximately 81,000 people aged 50 plus living with learning disabilities in England, the researchers created training for social workers and family members, plus a set of cards with pictures and questions to help people plan their future care.

It’s potentially life-changing, as are the team’s ongoing policy discussions with care providers and, of course, those who should have the biggest say – adults with learning disabilities.

One of the biggest barriers to tackling these inequalities was the COVID pandemic. Already facing extra challenges like anxiety and chronic health conditions, people with learning disabilities were hit even harder by lockdowns.

Assessing the impact was a team led by Professor Chris Hatton. Their research from December 2020 to November 2022 found that over half of adults with learning disabilities felt lonely, fewer had paid or volunteering jobs, and the number accessing day services or community activities plummeted.

More worrying, results from the last wave of interviews indicated that much-needed specialist support services still weren’t back to pre-pandemic levels.

“Family carers told us how their son or daughter changed under COVID restrictions,” says Prof Hatton. “Their lives became narrower until the spark went out of their eyes.

It’s brutal for these families because they can’t see a route to things getting better.

Thanks to game-changing work by Prof Hatton’s team, there are glimmers of hope. Partnering with Learning Disability England, they’re spearheading the COVID Commission for People with Learning Disabilities.

Crucially, it’s led by people with learning disabilities, who’ll be supported to investigate learnings from the pandemic and produce a set of recommendations. “These will be practical, positive actions we can put in place for if another pandemic hits,” says Prof Hatton.

The Commission is just one of many ongoing projects. From giving a voice to tired and frustrated family carers, to helping to improve autistic people’s intimate lives and preventing the over-prescription of medication to people with learning disabilities, each one tackles vital and previously under-researched issues.

As for Connor Sparrowhawk, he’s still touching people’s lives. Prof Ryan wrote a book, Justice for Laughing Boy, which was turned into a critically acclaimed play that debuted earlier this year at London’s Jermyn Street Theatre.

“It was the most stunning, powerful and heart-wrenching performance,” smiles Prof Ryan.

People were moved to tears and laughter.

“When Connor died, I questioned the point of my research. Now I can see it’s about working with people like him. They’re not just ‘people with a learning disability’ – their voice matters, and we need to listen.”

More stories

Discover more

-

![Headshot of Hannah Smithson]()

Breaking down barriers: making the justice system fairer

Find out more -

![Professor Saul Becker wearing a suit and facing the camera]()

A bright new future for children

Find out more -

![Professor Khatidja Chantler and Professor Michelle McManus facing the camera with their arms crossed.]()

Informing domestic abuse policy

Find out more -

![Robert and Oliver wearing lab coats in a laboratory with containers on the table in front of them.]()

Cutting harm from drugs

Find out more -

![Rob Drummond speaking behind a microphone in a radio studio.]()

Accent pride and prejudice

Find out more -

![Dr Krystal Wilkinson sat on a panel with three other women]()

Improving the wellbeing of women in the workplace

Find out more

About 200 years

Manchester Met celebrates two centuries of driving progress through excellent education and research.

-

![Siemens Chief Executive Carl Ennis posing with the firms degree apprentices]()

Driving economic growth

Find out more -

![Two nurses standing together and smiling]()

Transforming health

Find out more -

![A digital image of the university's arts buildings]()

Championing creative excellence

Find out more -

![Amer Gaffar and Liz Price stood smiling at the camera]()

Leading sustainability

Find out more