Making the justice system fairer

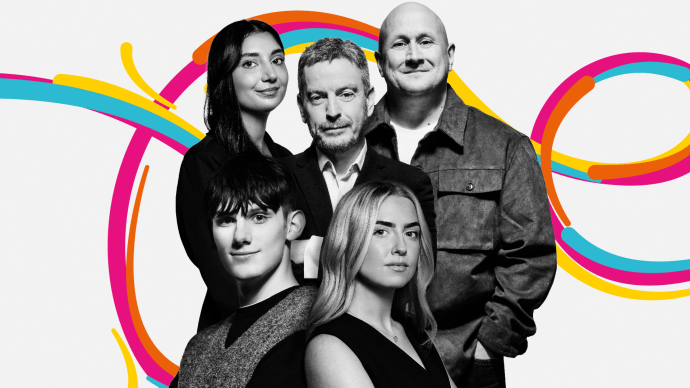

Hannah Smithson

Standfirst

Even after 20 years working with children in the youth justice system, there are times when Professor Hannah Smithson is moved beyond words. “During the pandemic my colleague Deb and I came out from interviewing teenagers in prison,” she recalls.

“We’d spoken to a group of child lifers – that’s hundreds of years between them in sentences, and individually more time ahead to serve than they’d been alive. We had to take a moment to process that, just sitting silently in the car before driving off.”

Anyone who’d witnessed a fraction of what Prof Smithson has in her career might have had the same reaction. Most recently, a report by her team revealed the shocking reality of lockdown prison life for children.

Main story

It paints a bleak picture of an overlooked sector of society.

Left alone for days, refused family visits, and denied basic education, children in custody during COVID lockdowns were failed by the youth justice system, the findings revealed. “What we found wasn’t a surprise, but it was still shocking,” says Prof Smithson.

“Some of the kids we spoke to were locked up alone for 23 hours a day because staff in their youth offending institutes had COVID or were shielding. At points, food was left outside their rooms and their so-called education amounted to wordsearches being slipped under their door.”

Accounts of those children imprisoned hundreds of miles from home, declining family visits because they couldn’t face seeing their mums through a plastic screen and not being allowed to hug them, hit hardest. “That really stayed with us,” she said.

It’s that drive to see a child as a child that sums up the ethos of Prof Smithson’s work.

“Because they’re children, and because they’ve often been marginalised from an early age due to challenging home lives, they tend to get overlooked. But they’re the experts in their own lives, and we need to listen to them. It’s not about condoning but understanding.”

Given the well-documented prison capacity crisis and cost of custody amounting to a staggering £200,000 a year per child, prevention and providing alternative interventions that keep everyone safe – not least the child – is increasingly urgent.

The researchers have been tackling this issue head on. Back in 2015 they partnered with Greater Manchester Youth Justice Services, working with justice involved children to develop a brand-new approach.

Studious focus groups went out the window, and in their place came boxing workouts, rap lyric writing and urban art – activities familiar and accessible to the young people. Engagement was high, fun was had, and participants opened up about their experiences in a way no one could have imagined.

Because they’re children, and because they’ve often been marginalised from an early age due to challenging home lives, they tend to get overlooked. But they’re the experts in their own lives, and we need to listen to them. It’s not about condoning but understanding.

Almost a decade on, the wave of change is still rippling. “Previously, the sector was resistant to listening to what these children had to say,” says Prof Smithson. “But we plugged away and were able to affect a cultural shift.

“Now, our approach of working with young people to capture their views and opinions is written into all the youth justice teams’ plans across Greater Manchester. We’re still giving training on this and working with policy makers, not just regionally but nationally in Parliament.”

As Anne Longfield, Executive Chair of the Centre for Young Lives, attests: “Hannah’s agenda-setting work on the impact of COVID on vulnerable children was hugely beneficial to us when we were developing our national plan to protect teenagers from harm.

“This insight into the role adverse childhood experiences can have in increasing vulnerability to exploitation, crime, and serious violence informed a crucial part of a project that has led to the new Government’s commitment to introduce a Young Futures programme in the coming months.”

It’s not just children already involved in the justice system the team are working to support. Game-changing research led by Prof Smithson’s colleague Dr Deborah Jump recently showed that many thousands of girls in England are at risk of serious violence, sexual assault, and criminal exploitation.

Working with the Commission on Young Lives, Dr Jump warned that a lack of recognition of the scale of the problem and an under-reporting of concerns about risks to girls is leaving many vulnerable children invisible to services and help.

“What we heard from those girls was extremely worrying,” says Dr Jump. “Yet again, they’d been sidelined by a male-centric justice system simply because they present differently to services than boys.

“This is largely due to issues with poor mental health and self-esteem, however by highlighting these inequalities and working with policy makers we’ve been able to embed gender-specific mental health training and support into services’ safeguarding plans.”

If all this sounds unjust, spare a thought for the people wrongly convicted of crimes solely because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time. For over a decade, sociologists Becky Clarke and Dr Patrick Williams have been committed to tackling the gaping racialised and gendered inequalities in how joint enterprise law is applied.

This insight into the role adverse childhood experiences can have in increasing vulnerability to exploitation, crime, and serious violence informed a crucial part of a project that has led to the new Government’s commitment to introduce a Young Futures programme in the coming months.

It’s the controversial legal doctrine that has seen thousands of innocent bystanders jailed for life because the courts decided they knew someone else was likely to commit a crime and intended to encourage or assist them. Effectively, it’s being found guilty by association.

Aside from the devastation caused to lives, a study by Clarke and Dr Williams recently revealed the colossal cost to the taxpayer of wrongful imprisonment under joint enterprise law – an incredible £250m each year at the last count.

Their tireless work with policy makers, campaigners and the affected families is leading to greater awareness and a stronger fight for justice. Following their briefings earlier this year, a private member’s bill was introduced by Labour’s Kim Johnson MP, which could reduce the risk of unfair joint enterprise convictions.

It’s glimmers of hope like this that spur the researchers on. “No doubt about it, this is difficult work,” says Prof Smithson. “But if we can make small inroads and improve the outlook for one child who’s had adverse life experiences, our job’s been worth it.”

More stories

Discover more

-

![Professor Saul Becker wearing a suit and facing the camera]()

A bright new future for children

Find out more -

![Chris and Sara stood smiling with four of their colleagues]()

Voices that count: supporting people with learning disabilities

Find out more -

![Dr Krystal Wilkinson sat on a panel with three other women]()

Improving the wellbeing of women in the workplace

Find out more -

![Professor Khatidja Chantler and Professor Michelle McManus facing the camera with their arms crossed.]()

Informing domestic abuse policy

Find out more -

![Robert and Oliver wearing lab coats in a laboratory with containers on the table in front of them.]()

Cutting harm from drugs

Find out more -

![Rob Drummond speaking behind a microphone in a radio studio.]()

Accent pride and prejudice

Find out more

About 200 years

Manchester Met celebrates two centuries of driving progress through excellent education and research.

-

![Siemens Chief Executive Carl Ennis posing with the firms degree apprentices]()

Driving economic growth

Find out more -

![Two nurses standing together and smiling]()

Transforming health

Find out more -

![A digital image of the university's arts buildings]()

Championing creative excellence

Find out more -

![Amer Gaffar and Liz Price stood smiling at the camera]()

Leading sustainability

Find out more