How our researchers are supporting conservation around the world

Header image

Standfirst

Compared with the destruction of vast swathes of rainforest, the declining numbers of insects on your car windscreen during a long summer drive or fewer bees in your back garden might seem like small things.

But evidence that biodiversity is under threat is all around us, for those who know how to look.

Main story

Around 1 million species are currently threatened with extinction, more than at any other time in history.

Species are disappearing at a rate that is 1,000 times the norm according to the United Nations Foundation, which cites the way most humans consume, produce, travel and live as the culprit.

It is against this backdrop that researchers at Manchester Metropolitan are stepping up, with their work helping to protect and preserve animals and plants all over the globe.

Saving threatened species

One such project led by Stuart Marsden, Professor of Conservation Ecology, is helping to save the endangered African grey parrot whose populations have plummeted anywhere from 90% to 99% in the last 25 years – pushing the species to extinction – his research found.

The evidence uncovered by Professor Marsden secured a vital total trade ban on the bird in 183 countries, helping it to recover in some areas.

It is this work that is helping the University to support conservation around the world as part of its Conservation, Evolution and Behaviour research group.

The group’s experts work alongside communities and partners in countries where species are under threat – and here in the UK.

Threats to the Amazon

Dr Alexander Lees is a Reader in Biodiversity at Manchester Metropolitan whose work has taken him from the Peak District to South East Asia. The majority of his work focuses on the Amazon basin and how biodiversity responds to global change, with a particular interest in birds.

Dr Lees identifies three key threats to biodiversity in the Amazon: the conversion of tropical rainforest to non-forest land uses, such as agricultural fields, the degradation of those tropical forests by fire and selective logging, and the subdivision of patches of forest into smaller and smaller patches, on top of which climate change acts as a ‘force multiplier’.

“Commerce is one of the big drivers of the loss, fragmentation and degradation of forests, and agribusiness has been a big driver of forest loss, producing beef for export to external markets or other crops such as soybeans, which is principally for animal feed. There are also big challenges with logging,” says Dr Lees.

“Brazil has some of the sort of most visionary environmental legislation, but loggers can be predatory and act unsustainably, principally because of a lack of governance in the frontier regions of Amazonia – if there’s no one there to enforce that legislation, that’s a big problem.”

Protecting the forests

This is where Dr Lees’ work has had a significant impact, providing an evidence baseline for a change in the law affecting secondary forests that cover more than a million hectares in the eastern Amazon.

“Our research has been fundamental in shaping forest policy because we have been able to show what age that secondary forest should be legally protected to protect biodiversity and carbon stocks.

“In this case, secondary forests are forests that are regrown from historical clearcutting, so a forest which perhaps was once a field with cattle in it was then abandoned and has then started regrowing. Quite often these forests are cut down. Our work, especially on secondary forests, has also been fundamental in providing the targets for the state governments to meet their own climate goals, with essentially these forests stocking carbon to offset emissions elsewhere.”

Government policy has a key role to play in preserving biodiversity, according to Dr Lees. “Policy is often isolated from its impact on the environment. We need to see the intersection between conserving biodiversity, maintaining ecosystem services, and ensuring development.

So often we just we chase economic goals without thinking about the costs to the environment, and that comes back to haunt us.

Fundamentally, we need a different kind of governance that understands the value of biodiversity and values that by protecting it.”

Humanity and biodiversity

For Julia Fa, Professor of Biodiversity and Human Development at Manchester Met, there can be no separation between humans and the natural world.

Professor Fa’s work focuses on emerging issues that impinge significantly upon the long-term future of global biodiversity, such as defaunation of tropical rainforests, the impact of loss of wildlife on people dependent on it, climate change, and the impact of diseases on wildlife and humans.

Her previous projects include working with 900,000 indigenous people in the Congo basin, where improving people’s prosperity, literacy and livelihood went hand in hand with promoting biodiversity.

“We worked on strategies with the Baka Pygmies in remote villages in south-eastern Cameroon to develop ways of managing natural resources sustainably, and generating food and income from subsistence and cash crops,” she says.

“Ultimately, it’s about integrating research on biodiversity with human development: the future of both people and animals is strongly intertwined.”

“Together with the Baka communities themselves, we came up with ways of securing these peoples’ way of life and safeguarding their food security at the same time as helping them become custodians of the biodiversity that surrounds them.

“Ultimately, it’s about integrating research on biodiversity with human development: the future of both people and animals is strongly intertwined.”

Experience wild nature

In terms of our own relationship with nature, Dr Lees is passionate about the connection between humans and the environment we live in.

“We need to connect people with nature more to make sure that everyone, no matter their age, has more experience of wild nature and therefore becomes more invested in its conservation,” he says.

“That’s a big societal challenge that I don’t think we do well enough because most children show an innate love for nature, but so often they’re not exposed to it. From schools to universities, offering more opportunities to spend time in wild nature, understand it and value it is something we need to pursue.”

More stories

Discover more of our research

-

![An aeroplane taking off, seen from inside an empty passenger lounge]()

Cleaner and greener flying

Find out more -

![A researcher operating one of the machines in the Manchester Fuel Cell Innovation Centre]()

The future of clean power

Find out more -

![Dr Paul O'Hare stood among wildflowers with Manchester post-industrial skyline behind him]()

Greening the city – Manchester’s changing climate

Find out more -

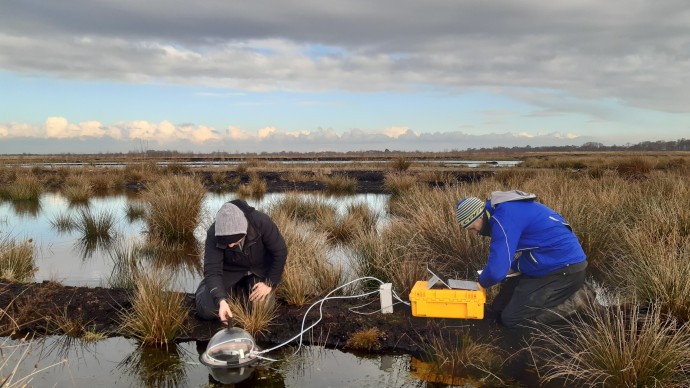

![Researchers taking measurements from a peat bog in the Peak District]()

A natural solution

Find out more -

![Professor Liz Barnes, head of Manchester Fashion Institute, in a fashion room]()

A circular future

Find out more

About 200 years

Manchester Met celebrates two centuries of driving progress through excellent education and research.

-

![200 years 1824-2024]()

200 years

Find out more -

![Siemens Chief Executive Carl Ennis posing with the firms degree apprentices]()

Driving economic growth

Find out more -

![Two nurses standing together and smiling]()

Transforming health

Find out more -

![A digital image of the university's arts buildings]()

Championing creative excellence

Find out more