Understanding aircraft emissions and their effect on the climate

How do we ‘do our bit’ for the environment and still enjoy our holidays?

About the research

We’ve lived through lockdowns, stretched our salaries, and survived political chaos. So, it’s no wonder most of us are dreaming of far-off climes.

But with sustainability high on everyone’s agenda, and climate change now widely accepted as the number one threat to civilisation, how do we reconcile our need to ‘do our bit’ with our desire to jet off on our jollies?

Meet David Lee, a Professor of Atmospheric Science at Manchester Met and a decades-long sustainability scientist and policy shaper whose seminal, globally influential work has helped set standards and agreements to reduce carbon emissions from aviation.

A self-confessed ‘reformed jet setter’, he went from clocking up 15- 20 flights per year early in his career to eliminating them altogether.

It’s these decisive acts by a researcher-in-the-know that sum up the urgency of the matter. While the Paris Agreement, an international treaty on climate change, set a target in 2015 to limit global warming to below 2 — preferably to 1.5 — degrees Celsius, it’s looking increasingly, and depressingly, out of reach.

Those targets involve emissions going down 45% by 2030 and reaching net zero by 2050. And here’s the rub. While CO2 emissions are on the decline in every other sector, in aviation, they’re soaring.

“We’re seeing an average aviation industry growth of five per cent every year,” said Lee. “That’s enormous when you compound it over recent times. Aviation’s been a significant sector since 1940, yet half of the total CO2 emissions from that sector happened in the last 20 years.”

Lee’s recently published research paper, led by him alongside an international authorship of 21 academics, revealed that 3.5% of the total impact of humankind on climate now comes from aviation. “It might not sound like much, but it’s highly significant,” he said.

Looking at the industry as if it were a country, it would be in the top ten emitters worldwide.

A big part of the problem, said Lee, is the sheer longevity of the aircraft themselves. Unlike cars that tend to be replaced every few years, planes stay in service for decades – over five in the case of the recently retired Boeing 747.

“It also takes somewhere between ten and 15 years to actually develop an aircraft,” said Lee. “Manufacturers, investors and policymakers need certainty extremely far in advance on how regulation and design will affect emissions.”

How Manchester Met steps in

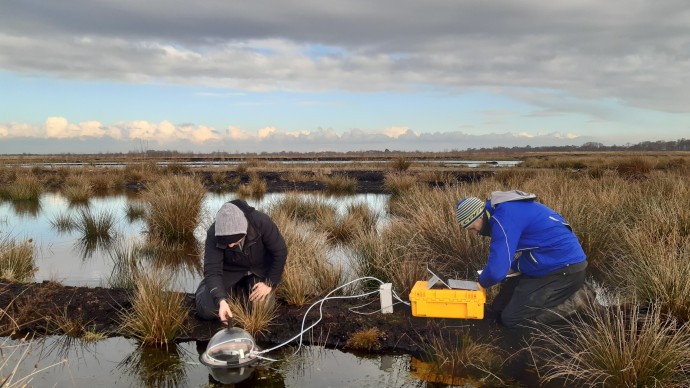

That’s where Lee and the Manchester Met team step in. Their painstaking and invaluable research involves measuring emissions on the ground behind aircraft engines and comparing them according to different types of fuel. They then analyse and incorporate these measurements into cutting-edge computer models of the Earth’s atmosphere to see how it’s affected.

The outcome may paint a bleak picture, but the team’s already been able to affect measurable international change. Their modelling of aircraft emissions and their resultant climate effects underpinned the design of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme for aviation, which delivered net savings of 193Mt CO2 (translation: a lot) between 2013 and 2020.

Their analyses for the International and Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) have directly informed technical specifications to mitigate climate change from the aviation sector over the next 15 years.

And their work shaped two new international regulatory standards for aircraft engine CO2 emissions — set to reduce emissions by 5% annually. In the context of such a damaging sector, these are seismic shifts.

We’re privileged in a way not many scientists are, in that we get heavily involved with international policy. We occupy quite a unique position in that respect. I like to know that what I’m doing makes a difference.

It’s these significant policy wins in an otherwise bleak landscape that make the work of Lee and his colleagues worthwhile. Citing the ‘basic conflict’ between the industry’s dependence on non-renewable energy and the overwhelming consumer demand for air travel, Lee is realistic about what changes can be made in the short term.

“We’re dependent on liquid fossil fuel for air travel, namely kerosene,” he said. “There’s currently no electric technology that would fly aircraft any decent distance. It’s all about power-to-weight ratio, and the batteries required are simply too heavy.

“Some manufacturers are working on so-called sustainable aviation fuels like liquid hydrogen. They could conceivably power flights, but you’d need completely new aircraft to start with. You’d have to redesign the models themselves and, as we know, that takes many, many years.”

Nowhere is the evidence of those fossil fuels more visible than in the sky above us. Turns out, those seemingly attractive white wisps that streak behind planes tell a surprisingly sinister story about the harm of another pollutant: non-CO2 emissions.

Short for condensation trails, these ‘contrails’ form behind aircraft at cruising altitudes where the atmosphere is cold and humid enough. Essentially clouds made of ice crystals produced by the engine’s soot plus water emissions, contrails can last for many hours.

“These clouds reflect the sun’s radiation back to space, cooling the atmosphere, but they can also trap infrared radiation reflected from the Earth,” explained Lee. “This ultimately warms the atmosphere, as the warming effect exceeds the cooling.”

While this process accounts for nearly double the current global warming effect from historic CO2 emissions, Lee maintains the fundamental problem is still that pesky carbon dioxide. “CO2 is the most pernicious,” he said.

“It’s a molecule that doesn’t go away very quickly, and we keep pumping it into the atmosphere. About 50 per cent of it disappears relatively quickly, as in 30 or so years. The rest hangs around for centuries, and the tail end lasts millennia.”

It’s as mind-boggling as it is sobering. In the absence of technology to physically suck CO2 from the atmosphere, and with air travel at an all-time high (38 million scheduled flights per year at the last count), what more can be done?

One solution is simple yet unpopular. “There’s a philosophical argument that we just don’t cost aviation properly,” said Lee. “If we’re to use our limited resources responsibly, it should cost a lot more than it currently does to fly.”

Logical, certainly. Ethical, without a doubt. Attractive to the aviation industry and us world-weary sun seekers? That’s a harder nut to crack.

Airport emissions

All too familiar with the dichotomy between saving the planet and exercising our flying ‘rights’ are Professor Paul Hooper and Chris Paling, airport sustainability experts at Manchester Met. Focusing on airports rather than flights, they work with policymakers and airport operators to address barriers to sustainability.

Everyone needs to play their part in solving this problem. That includes airports, airlines, transport providers linked to airports and, yes, even us travellers.

“The reality is that this industry wouldn’t exist if we didn’t want it to. It delivers significant social benefit, and right now, there’s no immediately viable alternative for many flights. Our aim is to support the industry, deliberately meeting them where they’re at and helping to facilitate change.”

Whereas Professor Lee’s work focuses on aircraft emissions in the sky, Hooper, Paling and their colleagues concentrate on the carbon output in and around airports — another significant and previously less understood contributor to climate change.

Their decarbonisation studies have led to equally significant policy shifts, galvanising airport operators worldwide to adopt more accurate and responsible emissions reduction methods.

We’ve had a significant say in the way the Airport Council International thinks about carbon accounting and emissions. Our research and advisory work have helped to change the way airports all over the world work to reduce their emissions.

Airport decarbonisation 101: make sure you’re reporting all emissions. As the researchers discovered back in the mid-noughties, this wasn’t happening. By only accounting for emissions within their control or ownership, airport operators were likely to report just 5-10% of emissions associated with the operation of the whole airport system.

The Manchester Met team stepped in, developing new reporting systems involving the entire carbon ‘footprint’ made by the unlikeliest airport value chain sources – from the sandwiches shoppers buy to the cleaning utilities and even the water flushed away.

There’s carbon generation in airports that we don’t even notice, like the way the building’s heated and lit,” explained Hooper. “Once it’s reported properly and analysed, alternatives can be found. Part of our role is to define what’s included in these reports, and we’ve successfully argued that flight emissions at airports should be in there.

“It’s a huge headache for airport operators, but they’re striving for change, and we’re in a position to be able to support them with that.”

By influencing and supporting operators to include granular-level detail like this, the Manchester Met team helped develop the Airport Council International’s lauded Airport Carbon Accreditation. Today, it boasts over 400 member airports in 87 countries which, collectively, represent around 50% of all commercial air passenger traffic. Safe to say, it’s a success.

But that’s not to say the work’s done — far from it. Airport decarbonisation strategies continue at full throttle, including Manchester Met’s influential partnership with TULIPS, a major EU-funded project to improve sustainable, low-carbon activities in and around airports.

There are even ongoing efforts to reduce the impact of aircraft noise, another problematic barrier to aviation sustainability. Manchester Met’s research on the use of new, alternative noise reporting directly informs noise management work at UK airports, including Stanstead and Heathrow, Europe’s noisiest airport.

The future

And when it comes to the future of flying, whether focusing on airports or planes in the sky, all three scientists agree there are wider ethical and sociological issues at stake. “I’m increasingly convinced there’s no easy fix, and that’s something we have to accept,” said Lee.

“As a society, we have this insatiable urge to consume travel simply because it’s possible. We have to ask ourselves if that’s reasonable. Appropriate pricing may be our best option until the technology catches up, and that brings its own problems. There’s simply no silver bullet for aviation.”

Stopping short of advocating Lee’s personal ‘zero flight’ policy — something he himself concedes even the most eco-conscious of us might baulk at — Hooper moots a concept he calls ‘holiday maths.’

He explained: “If, for example, you enjoy two weeks in the sun each year, and you like jetting off in March and September, maybe compress it into a fortnight. That way, you’ll take two rather than four flights — do the maths around your travel.

“This is about fundamentally changing the way we think about flying. We need to shift hearts and minds.”

Less lofty but equally responsible, there are smaller travel tweaks to be made, Hooper said, like getting the tram to the airport or leaving your vehicle there instead of being dropped off and collected.

From shaping international carbon emission policies to parking your car, it’s clear that however uncertain the future might look for the aviation industry, there’s always a way to contribute.

Lee added: “We’re working our socks off to upgrade technology, use better fuels, reduce emissions, and improve airports, but trying to deliver the Paris Agreement is very, very hard.

“All we can do is keep trying, and the science we’re working on here at Manchester Met plays a key role. We’re lucky because we have a unique role to play amongst universities.”

Lead academics and research group

Lead researchers

-

Chris Paling

Senior Lecturer

-

Professor Paul Hooper

Interim Director of the Ecology and Environment Research Centre

-

Professor David Simon Lee

Professor of Atmospheric Science